Selections from the records: some notable personalities

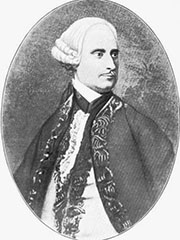

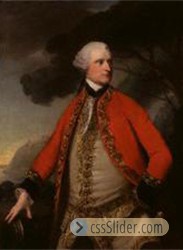

General James Patrick Murray (1721-1794)

James Murray joined the British army in 1739/40 and served in the West Indies and Europe. Sent to North America in 1757 as a lieutenant colonel during the Seven Years' War, he commanded a brigade in 1758 during the successful British siege of Louisbourg, in what is now Nova Scotia, under Jeffery Amherst. He was one of General James Wolfe’s three brigadiers in the British expedition against Quebec in 1759. After the British captured the city, Murray was made its military governor. When the French capitulated in 1760, he became military governor of Quebec district; he became the first civil governor of Quebec after its formal cession to Great Britain in 1763, later becoming the first British Governor of Canada. Murray opposed repressive measures against French Canadians, and his conciliatory policy led to charges against him of partiality. Although exonerated, he left his post in 1768 and was appointed governor of Minorca in 1774. He surrendered to French and Spanish troops there in 1782, for which he underwent a court of inquiry in England; after being acquitted, he was made lieutenant general (1772) and later a full general (1783).

Major-General James Patrick Murray 1782 -1834

"This gallant officer was the only son of General Hon. James Murray and was born,on the 21st Jan. 1782, at Leghorn, to which city his mother had retired from the siege of Minorca, whose defence was being led by his father, General Murray. She was Anne daughter of Abraham Whitham, esq. the British Consul-general at Majorca. He was educated at Westminster School; and, having determined to follow his father's profession, obtained an Ensigncy in the 44th regiment in 1796, and in the following year was promoted to a Lieutenancy in the same corps. In May 1798 he was appointed Aid-de-camp to General Don, with whom he continued in the Isle of Wight until June 1799; when he joined his relation and guardian Lt.Gen. Sir James Pulteney, and served as Aide-de-camp to that officer during the campaign in North Holland. He was present in the actions of 27 August, 10 and 18th Sept. 2nd and 6th Oct. and was in one of them slightly wounded. On Dec. 26, 1799, he was gazetted to a company, by purchase, In the 9th foot. He next accompanied Sir James Pulteney to the Ferrol, and was entrusted, by both the General and the Admiral in that expedition, with some important and confidential transactions. At the general election of 1802 he was returned to Parliament as one of the Members for Yarmouth in the Isle of Wight; but vacated his seat in the following March. At the peace of Amiens he was placed on half pay; and after studying for some time at the Royal Military Academy, was re-appointed to half pay in the 66th foot. In 1803 he espoused the amiable object of a long attachment, Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Edward Rushworth, esq. of Freshwater House, Isle of Wight, and granddaughter of the late Lord Holmes, by whom he has left twelve children. In Feb. 1804, he obtained by purchase, a Majority in the 66th, with which he was stationed in several parts of Ireland; and subsequently was appointed to the staff of that country as Assistant Quartermaster-genera1 at Limerick, which situation he relinquished in order to accompany his regiment on foreign service. With the same regiment he also served in Portugal; where, at the passage of the Douro, he received a severe musket wound, which not only completely shattered and deprived him of the use of his right arm, but ever after impaired his general health. His gallant conduct, on this occasion, is honourably recorded in the public despatch of Sir Arthur Wellesley, who, shortly after he had received the shot, came up to him on the field, and, taking him by the hand, said, -" Murray, you and your men have behaved like lions; I shall never forget you". On the 25th May 1809, Major Murray was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel; and on his return home, he was employed in the Quartermaster-general's department in Ireland. From 1811 to 1819 he was Assistant Adjutant-general, stationed at Athlone. In 1819 he received the brevet of Colonel, and in 1830 that of Major General.

His death was occasioned by a cold caught in his humane exertions to save the lives of two young officers, who were drowned in the lake in front of his residence".

from his obituary

Maurice Fitzgerald Wilson (1858-1945)

Maurice Fitzgerald Wilson was born on the 4th February, 1858, and died on the 23rd December, 1945. He was educated at Eton and at the Crystal Palace School of Engineering, and, after a short period at the Thames Ironworks, was articled in 1881 to Sir John Coode, K.C.M.G., Past-President Ins. S.E., spending most of his pupilage on the harbour works at Table Bay and Port Elizabeth. From 1883 to 1886 he was engaged on constructional work at Tilbury Docks for Messrs. Kirk and Randall and Messrs. Lucas and Aird, for whom he also worked on the Bodmin and Wadebridge Railway. In 1888 he was appointed resident engineer on the construction of the breakwater at St. Ives, Cornwall. From 1892 to 1895 he was resident engineer on the dock works of the London and South western Railway at Southampton. In 1896 he was appointed superintending engineer in charge of the survey for the Admiralty harbour, Dover, and later for the construction of the works, on which he was engaged until 1905. In 1906 he joined the firm of Coode, Son and Matthews, of which in 1924, on the death of Sir Maurice Fitzmaurice, Past-President Inst. C.E., he became senior partner. For nearly forty years he was engaged in the design and construction of harbours, docks, sea defence works, bridges and barrages, including dock extnesions for the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board; the Admiralty harbour of refuge at Peterhead; Fishguard harbour; the Lyttelton and gisbourne harbours, New Zealand; wharves and docks at Singapore; the Jahore causeway; Colombo harbour; entrance works and wharves at Lagos; harbour works on the Gold Coast, in Sierra Leone, and in Gambia; and work for the Whangpoo Conservancy Board, Shanghai. In 1921 he was appointed a member of the consultative committee ofengineers of the European Commission for the Danube. From 1929 to 1933 he was in charge of the technical investigation of the proposed Severn barrage, upon which the report issued in 1933 was based.

Mr. Wilson was elected an Associate Member of the Institution on the 5th February, 1884, and was transferred to the class of Member onthe 12th February, 1895. He was elected to the Council in November 1928 and became Vice-President in November 1937, but declined nomination for election as President in November 1940 owing to ill health. In the previous February he had been elected an Honorary Member of the Institution. In 1919 he presented a Paper on the Admiralty Harbour, Dover, for which he was awarded the George Stephenson Gold Medal and a Telford premium. He was a member of the Sea Action Committee and later acted as its Chairman. For many years he took a leading part in the work of the British Standards Institution, of which he was Chairman from 1922 to 1933, and honorary life chairman of its Engineering Divisional Council.

In 1884 he married Florence May, daughter of the Venerable Hopkins Badnall, Archdeacon of the Cape, and had two sons. Mrs. Wilson died in 1941.

Captain Maurice Fiennes Fitzgerald Wilson (1886-1975)

As a child, visiting my grandfather Fiennes (as he was known), there was always great pride in his achievements and huge affection for a generous and thoughtful soul, and one with a huge sense of humour and fun. Fiennes always enjoyed gently pulling a leg or using irony to tease someone, and he often used humour to defuse an awkward situation. Fiennes had installed bunk beds for my brother Michael and me when we stayed, and he put toy telephones so that the brother on top could speak with the one on the bottom; this was a huge joke to us young children. He used to tear a pound note into two and give each one of us one half, so that we would have to co-operate with each other and trust each other in order to stick it together, go to a shop for change and then distribute the money evenly: but he did it with a sense of fun and mischief, rather than to teach a lesson.

Fiennes was born in Gravesend, Kent, and educated at Winchester College. He joined the Royal Navy as a 15-year-old in 1901. He was a Naval cadet on board HMS Britannia. He left the Navy around 27 years later with the rank of Commander; on retirement he was given the honorary rank of Captain.

The greatest disappointment in his life was the fact that he had applied to go on Scott’s trip to the Antarctic, as navigator, and had so nearly been accepted; to quote from the various correspondence, which is still kept by the family: “... also told me that he was pushing your name forward and expected you would be the next [naval officer] to be applied for, so i hope we may hear something definitely very shortly...” and “I don’t think Captain Power was able to find out for certain about you and the South Pole, but from what Evans said to me I think you will get it all right....” But when rejection came at the last instant, as a result of the politics of whether Naval Officers or civilians should fill the various posts, Fiennes was bitterly disappointed, but, so typically for him, threw it off with a homorous bit of semi-legible doggerel scribbled on the back of the rather formal letter of rejection: “ ... you can’t all live in England, nor a house in Golden Square; you can’t all be a Prince of Monaco..... don’t sigh for what you haven’t got.... but just you understand the best of wealth is jolly good health, it’s worth all the riches in the land.”

Fiennes’ career was with the Royal Navy. He distinguished himself throughout his career, but never achieved the very top ranks, although he had some very influential advocates; quiet, extremely conscientious, extremely competent, and liked by all – these are the traits which all who came into contact with him observed: “to my entire satisfaction. A most capable and reliable Navigating Officer... with much zeal and tact”.... “An able, cool and zealous Officer”... “I cannot speak too highly of the absolute reliability with which he carried out his work, which always requires the greatest mathematical accuracy and frequently called for the exercise of cool judgement in emergency... it was a matter of the greatest regret to me that the extraordinary congestion in the list of 1927 led to his missing the promotion for which he undoubtendly deserved” ... “He is sober and steady as a rock, and absolutely reliable and is as cheerful after a long and worrying night on the bridge as if he had spent the night in bed.... He is not one of the world’s talkers, and his shyness and modesty are the only faults I have discovered after a long association”. This latter quote by his commanding Officer Vice-Admiral Kelly, in 1928, after they had served for the League of Nations Commission, finishing off at the Admiralty on retirement.

Commander Wilson, as he was in 1917, earned his DSO (Distinguished Service Order) when Navigator and 2nd in Command of HMS Calypso. On 17th November 1917, when in action in the Heligoland Bight, the Captain was killed by a shell, and Commander Wilson was wounded by the same shell in both legs and in several other parts of his body, but remained at his post for over an hour until he had brought his Ship out of action, when he was taken below. He was in hospital for four months, and on sick leave for two, as the result of these wounds, so his courage and powers of endurance were shown to be remarkable.

On retirement he took up chicken-farming in Sussex, as well as pursuing interests in genealogy and book-binding; he had considerable involvement with local affairs. He had a life-long interest in painting and drawing and was an immaculate draughtsman and cartoonist.

On the advent of World War II he was recalled to the Navy and worked at the Admiralty till the end of the war. He was in the Trade Division and took a major part in organizing a system of refuelling naval escorts of trade convoys at sea. At the end of the war he was made a Commander of the Order of Orange Nassau wtih swords by Queen Wilhelmina of Holland.

After the war, Fiennes had a house built for himself in Watlington, Oxfordshire, where he filled his time with bookbinding, genealogy, reading and driving and caring for a beautiful old Bentley car. He died in February 1975, having lived an extremely full life, and was never embittered by the two big disappointments of missing out on Scott’s expedition and promotion to the highest ranks of the Royal Navy, but remaining positive, cheerful and of good humour to the end.

Richard Badnall (1797-1839)

Richard Badnall was a well educated man, poet, author and inventor who played the flute and whose romantic disposition is evident in his writings and in his choice of home. His book "the Legend of St.Kilda", "Zelinda: a Persian tale", and his poem "The Pirate" illustrates his Byronic, romantic, view of the past and the Staffordshire homes he chose for himself - Ashenhurst, Woodseaves and Cotton Hall - give further clues to his nature. His sister Mary Elizabeth Cruso, described him on one occasion as "as usual full of schemes " and of "talking up and down the town of his plans for enriching himself and his family". In 1837, after hearing that her brother proposed to stand as a Parliamentary candidate for Newcastle-under-Lyme, she described him as "strange in his proceedings". He was also, for a time, a silk manufacturer and dyer and perhaps would not have ventured into railway engineering had not his first partnership with his brother in law Henry Cruso and Francis Gybbon Spilsbury come to an early and abrupt end in 1826 with the bankruptcy of the partners and the parents of both Badnall and Spilsbury. Following the announcement of his bankruptcy, Richard Badnall Junior had tried strenuously, both in this country and in France, to remedy matters, pay his creditors and sustain his wife and their young family. The contents of the family home, Ashenhurst, were sold off and for several years Badnall's life was extremely unsettled before he went to live with his father in Liverpool. In 1832 his petition as an insolvent debtor was heard at Lancaster Court and later that year a patent application revealed that, although he may have been without an occupation, his mind was as active as ever. It was this patent that formed the chief item of discussion between Richard Badnall and Robert Stephenson, younger brother of George Stephenson which led to the formation of the Stephenson & Badnall partnership. The debate about Richard's proposed "Undulating Railway", in which he proposed a line which would have a constant though shallow gradient, became a matter of national and parliamentary discussion. Although the idea was eventually shelved, with Richard's contemptuous cirtics seeming to put him in his place for "bad science", Richard possibly had the last laugh, as his idea was taken up by Benjamin Baker, who built the first line of the London Underground, using the principle of an undulating railway. Unfortunately Richard suffered all his life from gout, and the combination of this and the stress under which he lived from 1827 resulted in his death in 1842, at the relatively early age of 42.

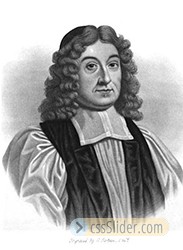

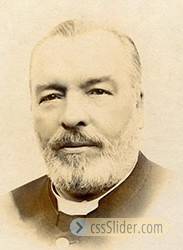

The Venerable Hopkins Badnall (1821-1892)

The life story of the Venerable Hopkins Badnall begins in the little Staffordshire town of Leek, on the western edge of England's Peak District. Hopkins was born on September 21, 1821, the second son of Richard Badnall (1797-1839) and his wife Sarah, the daughter of a Uttoxeter solicitor, Isaac Hand.. Richard (famous for the invention of the “Undulating Railway”, for the testing of which he had borrowed the “Rocket” engine from George Stephenson) was a from a family of prosperous silk manufacturers, but had subsequently fallen on hard times; Richard was an inventor and dreamer who died young but who lived life to the full.

Hopkins studied under the tuition of his uncle, the Rev. William Badnall of Wavertree, Liverpool. At the age of twenty, he entered the University of Durham, where he won several awards and graduated as a B.A. in classical and general literature in 1844. He was elected a Van Mildert Scholar for his academic achievements and suitability as a divinity student.

Hopkins Badnall obtained a Licentiate in Theology in 1845 and also became a Fellow of University College. In 1851, after he had left the university, he was awarded his M.A. and eleven years later, he gained a doctorate in divinity by diploma. The young man was ordained deacon in 1845 and priest in the following year. His career in the Anglican Church began with his acceptance of a curacy under the Rev. Robert Gray in the industrial town of Stockton-on-Tees, County Durham.

It was late in 1846 that Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts, the great Victorian philanthropist and friend of the novelist, Charles Dickens, made a substantial donation to the Colonial Bishoprics Fund for the endowment of two new sees. One of these was to be at the Cape of Good Hope and in June, 1847, Gray was consecrated Bishop of Cape Town in Westminster Abbey, London. Hopkins Badnall joined the new Bishop's party as his domestic and examining chaplain and on December 20 sailed from Portsmouth in the "Persia", bound for Madeira, the Cape and Ceylon. The long voyage ended for the newcomers to South Africa on Sunday, February 20, 1848, when the small vessel cast anchor in Table Bay. The first phase of Hopkins Badnall's connection with South Africa had begun.

He took up residence at Protea, later known as Bishopscourt, the home of Robert and Sophia Gray, and officiated at Claremont, where a small church was eventually built. He does not seem to have been popular among the clergy at this period, but his position as chaplain to a Bishop intent upon rousing a somnolent church was a difficult one. Nor was he entirely successful in another field to which he was introduced as a result of Gray's zeal.

It had long been the dream of Anglicans at the Cape to found a school which would be a counterpoise to the undenominational South African College, established in Cape Town in 1829. The new Bishop was determined to make this a reality and in 1849, opened the Diocesan Collegiate School on the Protea estate. A brilliant scholar from Winchester and Oxford, Henry Master White, who had come out to the Cape to work for Gray at his own expense, was appointed Principal; Hopkins Badnall added to his other duties that of Vice-Principal. The two men had strikingly similar careers. White, a future Archdeacon of Grahamstown, was also to serve upon the university Council in Badnall's time. His death followed closely upon that of his old colleague.

The school, soon to move to Woodlands, was very small, for the arrival of two little boys in August, 1849, only brought the total number of pupils to nine. It was a modest start for the Diocesan College of today. Two future members of the university Council were boarders there: John X. Merriman, the politician, and John Espin, later to distinguish himself in the church and as Headmaster of St Andrew's College, Grahamstown. Another pupil was W.H. Ross, who became the medical superintendent on Robben Island. Both Espin and Ross have left recollections of those days which suggest that Badnall did not endear himself to the young as a teacher. While the school remained at Protea, he used to take the senior class for an hour each morning; after the move to Woodlands, he rode over for lessons twice weekly. "The young fellows", Canon Espin recalled, "dreaded his coming since he appeared to them to be lacking in sympathy", while Dr Ross remembered his nickname, "Carker", and the brilliant glitter of his teeth as he smiled a cold, conventional smile! Yet to leave that impression is to do Hopkins Badnall an injustice. John Espin came to know him better on many an adventurous mountain climbing expedition and grew to love him well. Gray found him gentle and considerate and there is eloquent testimony of the affection in which he was held by his parishioners from Claremont days onward.

The increasing burden of church duties compelled Badnall to resign as Vice-Principal in 1853. In February of the following year, he married Sarah Elizabeth, the daughter of a Port Elizabeth merchant, John Owen Smith. Sarah died in London on December 7, 1903, at the age of 70. Two of their three sons, Herbert and Reginald, passed the Law Certificate examination of the University of the Cape of Good Hope. Herbert, who died in 1938, became Magistrate at George in the Cape. The other son, Lancelot, was a prominent sportsman. He was born in 1871 and attended Durham School in England. The Badnalls had five daughters, the youngest of whom, Evelyn Elizabeth, married Captain Frank Leonard Northcott of the Norfolk Regiment at St Mary Abbot's Church, Kensington, London, in June, 1898.

Soon after his marriage, Badnall decided to return to England, where he became Rector of Goldsborough and later curate in charge of the parish of Cawthome. He retained his connection with the Cape as the Bishop's commissary, however, and was in frequent demand as a speaker and preacher on missions. He had great gifts as an orator, sufficient to gain him the praise of the eminent Cape parliamentarian, Saul Solomon. In 1862, the Grays visited England and the Bishop was able to persuade his former chaplain to return to the colony. The Archdeacon of George, Thomas Earle Welby, had been elevated to the St Helena see and Hopkins Badnall was appointed in his place. He left his homeland for the second time in October, 1862, to take up his new duties.

Now began his period of greatest usefulness in the life of the church in South Africa, in the course of which he was able to display his learning as a theologian and his ability as an ecclesiastical jurist.

It was in 1862 that the unorthodox views of Bishop John William Colenso of Natal caused a public sensation in Britain and the colonies alike. The Bishop of Cape Town decided to take action against him and Badnall was chosen as one of Colenso's three accusers. His colleagues in the case were the Dean of Cape Town, the Rev. Henry A. Douglas, who was later to go to India as the Bishop of Bombay, and the Archdeacon of Grahamstown, the Venerable Nathaniel J. Merriman, John's father and the future Bishop of the eastern Cape city.

The proceedings took place in the cathedral at Cape Town between November 16 and December 16, 1863. Badnall was the last of the accusers to speak and his lengthy indictment lasted the best part of a day and a half. The result was a foregone conclusion and Bishop Colenso was formally deposed, a judgement subsequently reversed on appeal to the Privy Council in Britain. The differences between Gray and Colenso went further than matters of doctrine and Biblical interpretation. The question of authority within the church was involved and the Colenso trial marked a significant stage in a growing split within the Anglican community.

Hopkins Badnall's years at George were happy ones but he suffered from lumbago and the many journeys he made, often in inclement weather, aggravated the complaint.

In 1869, Badnall was appointed Archdeacon of Cape Town and Rector of Rondebosch in succession to the Venerable J.H. Thomas. He was also made a Canon of the cathedral in the colonial capital. He was now a leading figure and was to be offered the Bloemfontein see, a preferment which he declined. In the course of his career he published a number of sermons, tracts and addresses and had already appeared in print on the position of the church in South Africa. He played an important part when the first Provincial Synod was held in Cape Town early in 1870 and was largely responsible for the canons which were adopted there. These, together with a constitution, mainly the work of the Bishop of Grahamstown, Henry Cotterill, brought into being the autonomous Church of the Province of South Africa, with Bishop Gray as Metropolitan. The creation of this new body emphasized further the differences in outlook among Anglicans. Many Evangelicals looked with disfavour upon the High Church views expressed within the Church of the Province; many, too, saw no reason to change the existing order of things.

Badnall was actively involved in this conflict in 1879. In that year, he presided at the trial of the Dean of Grahamstown, Frederick Henry Williams, who refused to accept the jurisdiction of the Church of the Province over the cathedral there. As in the Colenso case, a verdict against Williams by the ecclesiastical court was overruled by the civil power. Both the Cape Supreme Court in 1880 and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in 1882 regarded the Church of the Province and the Church of England as separate institutions in law.

In 1872, Badnall lost his eldest daughter and his old friend, Robert Gray. He was deeply distressed. In the long interregnum which followed the Bishop's death - again reflecting discord within the church - the Archdeacon acted as Vicar-General. He enjoyed wide support as a candidate for the vacant bishopric; Gray, too; had thought of him as a likely successor. It was not to be, however, and the Rural Dean of Oxford, William West Jones, became the second Bishop and Metropolitan. Badnall co-operated with him loyally in many fields, although they did not always agree.

Anglicans who, like Badnall, deplored schism and were prepared to compromise, felt that the surest road to unity lay in the deletion of a clause in the constitution of the Church of the Province which gave it freedom to interpret doctrine in its own way, with no outside interference. The new Bishop was opposed to any such amendment, but Badnall campaigned strenuously in his last years at the Cape for the removal of the controversial third proviso. In this, however, he was unsuccessful.

Nevertheless, his known moderation enabled him to keep his Rondebosch congregation together and gained him the full backing of those who still looked upon the parish as an integral part of the Church of England. He was greatly loved and respected there and it was through his efforts that St Paul's Church was extended and its furnishings improved.

A few years after he had become Archdeacon of Cape Town, the Venerable Hopkins Badnall was brought into contact with the University of the Cape of Good Hope. In those days, instruction and examination were kept strictly apart and Section IX of the Incorporation Act of 1873 prevented the governing Council from appointing active professors as examiners unless others were unobtainable. Good scholars outside the colleges were therefore much in demand and the Rector of Rondebosch soon found himself setting papers and marking scripts for degree examinations in arts. The regularity with which the same gentlemen were selected for these tasks did not escape public notice and on one occasion the examiners were referred to in the Cape press as "recurring decimals"!

Badnall also applied to Council for admission to a Cape M.A. on the strength of his Durham qualification at this level - degrees in divinity being at that time unobtainable from the new institution. This was common practice in the lifetime of the University of the Cape of Good Hope and gave admitted graduates a voice in the deliberations of Convocation. The Archdeacon's application was accepted when Council met in December, 1874, and he was active in the affairs of the body of graduates for a number of years. He was chosen President of Convocation in February 1881, in succession to the Chief Justice, Sir J.H. de Villiers, and held that office until October, 1882. He was assisted by the Presbyterian minister, the Rev. J.M. Russell, who was then Secretary. De Villiers had also been appointed to the first Council in 1873; Russell took part in university government at a later period. At its meeting of March 17, 1875, Convocation had elected Badnall a member of the university Council. In the following year, however, he took leave in England for reasons of health and was obliged to relinquish his seat. Badnall's absence abroad was not a lengthy one and when the second six-yearly Council was selected in 1879, he again took his seat as a Convocation member.

The admission in 1882 of the Durham M.A. obtained by the Rev. Dr C. Maurice Davies was hailed by the opponents of the Church of the Province as a "significant triumph of learning and letters over ... bigotry". It was also seen as an encouragement to Dean Williams of Grahamstown, for Davies was one of his clergy. The university Council found itself further enmeshed in the Anglican schism when Davies became the centre of a sordid court case in the eastern city. The Bishop of Cape Town was not silent on the whole issue and some of his remarks found a wider audience than that in the Bureau Street debating chamber. One of his comments led to a threat of legal proceedings. This brought up the question of the sanctity of Council meetings and the propriety of admitting newspaper reporters. The last suggestion was at all times strongly resisted. Not every application for the admission of degrees was accepted. In March, 1884, another Anglican, the Rev. P.J. Oliver Minos, asked for recognition of his M.A. and Ph.D. of the American Anthropological University of St Louis, Missouri. Minos was in 1883 the Headmaster of Bishop Henry B. Bousfield's school for boys in Pretoria, St Birinus', and in charge of the cathedral choir. Council, however, declined to place the certificates of a well-known degree mill on a par with Cape degrees!

When Council met at the end of July, 1881, Langham Dale was re-elected Vice-Chancellor for the customary two-year term. Dale's resignation as Vice-Chancellor led to the election of Hopkins Badnall as his successor. Council, in its agitation, first chose him to complete Dale's term of office only, but later realized its mistake and extended his incumbency for the statutory two years. Badnall was thus Vice-Chancellor from 1882 until 1884.

Hopkins Badnall's period as Vice-Chancellor was not marked by any great changes in university administration. The institution over which he presided was already encountering considerable hostility as a factory of certificates of all kinds, but it was unwilling to relinquish any of its examining functions. When Laura A. Robinson, Principal of All Saints' School, Wynberg, asked in 1884 whether her pupils were free to sit the Cambridge Locals, Council sprang to the defence of its own tests for schools! At undergraduate level, a new examination was first held in 1883 - the Intermediate B.A. The work of Council was growing more complex at this period and in January, 1883, the first Standing Committee was appointed.

An Extension Act in 1875 had tried to make the University of the Cape of Good Hope a more South African institution, but the slower rate of educational advance outside the colony and a resistance to its Englishness impeded efforts made in this direction. Vice-Chancellor Badnall did, however, exchange letters with President J.H. Brand of the Orange Free State on the subject of bursaries to students living in that country.

Although no girls graduated until after Badnall's day, our forefathers were coming to agree that sustained mental activity was neither injurious to their health nor beyond their capabilities! Agnes Ellen Lewis passed the Intermediate examination in 1884; two years later, she would become the first woman to obtain a B.A. in South Africa. She studied privately to this end, but the colleges soon began to open their doors to girls who wished to follow in her footsteps.

Langham Dale returned as Vice-Chancellor in 1884, although Badnall remained a member of Council. He was chosen once more by Convocation in the election for the third Council of 1885, but resigned almost immediately. His health was far from good and he decided to leave the colony. The Council vacancy caused by Badnall's departure was filled by the appointment of the Congrega-tionalist minister, the Rev. Wilberforce Buxton Philip, youngest son of the famous Scottish missionary, John Philip.

Badnall sailed for England in the latter part of 1885 and settled again in the West Riding as Rector of Fishlake, near Doncaster. In 1888, however, he moved to the Maida Vale district of London, where he lived in retirement. It was there, on September 27, 1892, that he died.

Hopkins Badnall was buried four days later in the family vault at Leek Parish Church. The opening sentences at the funeral were spoken by the Vicar of Leek, the Rev. C.B. Maude, once Rector of Kimberiey and Precentor of the cathedral in Cape Town; the Lesson was read by the Rev. S. Bond, a former Diocesan College Vice-Principal who had sat with Badnall in the Council Chamber of the University of the Cape of Good Hope; the service at the grave was conducted by Archdeacon Thomas, then Vicar of Hillingdon in Middlesex, whose place he had taken at Rondebosch. It was a last tribute to one who had devoted many years to the service of God and the cause of education in a distant land. His work should not be forgotten.

Basset Fitzgerald Wilson (1888-1972) & Muriel Gertrude Wilson (d.1977)

Early in May 1972, in the national obituary columns, appeared the name of Brigadier Bassett F. G. Wilson OBE. MC. Croix de Guerre, who had just died in London, aged 83. The paragraph following told of his service with the King's Royal Rifle Corps and the 4th American Corps in World War 1; of his service on Montgomery's staff and as Provost Marshal of the 21st Army Group in World War II; of his subsequent chairmanship of the RMP Association. Then, as an after-thought "artist who held exhibitions of paintings under name, Bassett."

When the Brigadier's widow, Muriel, died in October 1977, her obituary made no mention at all of the fact that she too, had been an artist. Yet in the 1930's Bassett and Muriel, to give them the names by which they chiefly signed their work at that time, had been accounted among the foremost of European painters.

Both were virtually self-taught. Bassett, after school at Rugby where he was an almost exact contemporary of Rupert Brooke, though not in the same house, went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he read Law. After graduation he had a short period as a very junior diplomat, then joined a flourishing law practice in London, before becoming a soldier in 1914 at the outbreak of War.

Severely wounded in France, he was advised by the M.O. to take up sketching in convalescence, as a way of improving the impaired co-ordination between eye and hand. He found he had a natural aptitude for drawing and painting, which he put to such good use when he returned to active service that he was able, in 1917, to mount an exhibition of Drawings and Watercolours of the Western Front at Walker's Galleries in Bond Street. As a serving officer he could not exhibit under his own name; and therefore chose the nom de pinceau Basfi du Bleu (significantly French, one may think, in the light of his later artistic development).

Muriel, one of the three children of Sir Francis Samuelson, 3rd Baronet, and his Canadian wife, Fanny Isabel Merritt Wright, had the usual upbringing of a girl or her time and place in Society. She too was found to have an aptitude for painting, chiefly watercolour landscapes and flower pieces. Her first recorded exhibition was a joint one with Bassett, again at Walker's Galleries, in 1921. No press cuttings survive, but it would seem to have been a success, since each had at least one watercolour reproduced in art magazines "Muriel's Violets in Bowl in "Drawing and Design¡", Bassett's Red Roofs and Poppies in "Colour".

In the 1920's both consolidated their position as good traditional English painters, with submissions to a group show at the Goupil Gallery in 1925 (where their fellow exhibitors included future R.A.'s Cosmo Clark and Vivian Pitchforth); Bassett in 1927 with a one-man show at the Fine Art Society in Bond Street of Watercolours of Italy, Spain and London which earned him the good opinion of the critics ("An amateur artist of exceptional talent, he can give points to many fulltime professional painters"); Muriel in 1929 by inclusion in Lord Duveen's British Artists' Exhibition at the Walker Gallery, Liverpool, and with a major show at Alex. Reid and Lefevre in London, which elicited high praise in the Sunday Times from the critic and historian of the Modern Movement, RH Wilenski, and from which a flower piece was bought by the Contemporary Art Society and presented to Leicester City Art Gallery, where it remains in the permanent collection.

This then was their situation at the end of the decade. Muriel, a Society painter of professional standard, was gaining renown for her decorative flower pieces. Bassett, a successful lawyer, was a Sunday and holiday painter, specialising in landscape watercolours and drawings. They lived in a fine small Town house in Knightsbridge, carrying on an easy and agreeable existence with their only son, Paul. Yet encouraged by good reviews "the praises of such as Wilenski, PG Konody of the Observer, Rom Landau of the Frankfurter Zeitung, the connoisseur/collector Dr. GC Williamson" and most of all by an overwhelming and passionate love of painting, they relinquished all these seeming advantages, sent Paul to boarding-school, and removed to Paris.

Their arrival at 23, rue Campagne-Première in Montparnasse marks their transition from above-average amateurs to superb professionals of the then unequalled Ecole de Paris. Not, of course that the change took place overnight. But the new environment resulted in an immediate lifting and liberation of the spirit. I know from my own experience, twenty years later, of the difference between London and Paris for a practitioner of the arts.

A guest at a dinner party in London, introduced as a writer, a musician, a painter, invariably faces the question, often enunciated, always implied "Yes, but what do you really do for a living?". In Paris "the Muse must be protected". This was said to the present writer not by some great patron of the arts, but by the keeper of a now defunct flea-bitten rooming house in the rue Monsieur-le-Prince as he transferred me, at no extra charge, from a noisy uncomfortable room on the street to the best his establishment could offer, an inner courtyard room with a window overlooking the minute garden.

Even more so was the Muse respected and protected in the Paris of the 1930's. And quickly the Wilsons made friends with their fellows in the Quarter "with André Lhote, in whose studio both worked from time to time; with the author Henri Heraut; with the photographer Marrc Vaux; and with Man Ray, under whose guidance Muriel became an expert creative photographer.

Naturally in such an environment, and able all day and every day to draw and paint uninterruptedly, their work flourished. In Spring 1930 they crossed to the USA for exhibitions at Knoedler's in New York and Chicago, in the catalogue foreword to which RH Wilensky advises collectors "buy them now, and be accounted men of foresight when the Wilson become more famous in a few years time."

In 1934 began the long sequence of exhibitions which were to give body to that prediction. In January at the Reid and Lefevre Gallery in London; in March at the Darlington Municipal Art Gallery, where their "modern" work caused uproar, and from which a Bassett watercolour of the Dordogne in the old style was bought for the town's permanent collection where it is still to be seen. In May both exhibited in the Salon des Tuileries in Paris, where Bassett was compared favourably with Jacques Villon by the French critic of the Gazette des Beaux Arts; in June at the Galerie Gerbo in Paris, where Bassett's Stacked Chairs, of which there is a later version in the present exhibition, was selected for particular mention in Sud; in July in a group show of English and American artists in Paris at L'Association Florence Blumenthal; in November with the Rhyma Group at Helsingfors in Finland.

The two Wilsons and Lhote were invited to represent the best and most modern in European art by a large group of Finnish artists. Matti Waren, secretary of the group, wrote after the show: "We are sure that your beautiful pictures, which you have so kindly sent to us to make our exhibition a great event in our art life, will have a stimulating effect on our painting ... The work of a pioneer is not a grateful one, if you consider the economical result, but its significance cannot be overestimated."

In the following year an even more important invitation was extended to Bassett and Muriel. A committee of French artists organised the first Salon du Temps Présent, the avowed aim of which was "to wage war on the revival of academicism". The Wilsons were the only English artists invited to submit work for consideration by the all-French artist jury. Both had work selected by that jury for exhibition alongside Dufy, Friesz, Miro, Bores, Kisling, Delaunay and Matisse. Their acceptance as full members of the School of Paris was complete.

In the following two years (1936/7) they were again both selected for the 2nd and 3rd Salons du Temps Présent (the latter being mounted in Durand-Ruel¡'s famous gallery). They showed also at the Paris Salons d'Art Mural and des Indépendants; at the Office of Spanish Tourism, and at the Galerie Katia Granoff. It was at this time that Bassett began the systematic use of collage, initially as a means of working out his compositions, but developing it into a full-blown medium as shown in Salzburg and Passage Interdit, collages in the present exhibition, and much later (in the 1960's) often incorporating some of Muriel's photographic prints of the 1930's.

Muriel for her part, joined on each of his school holidays by Paul, became enraptured by the celebrated Paris circuses, where she made photographs which she used as aide-memoires for the creation of such paintings as the masterly Cirque d'Hiver I and II in the present show. Each long vacation too, Paul himself, showing some aptitude for drawing and painting, joined his parents in a journey to some hitherto unexplored part of Europe - Italy, the Adriatic Coast, Yugoslavia, Turkey, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and once, Russia (the chief outcome of which was Bassett's massive Allegorical Ikon, not in the present show).

The 1939 war put an end to all this activity. Bassett, though two days beyond his 51st birthday, and unlike some of his Paris-based compatriots who took the first boat-train out of France to America, and were not seen again on this side of the Atlantic until 1946, joined the British Expeditionary Force in his old rank of Captain. Muriel at first organized refugee reception in France, and after Dunkirk, worked with the Motor Transport Corps in England. Paul joined the army, in the fullness of time becoming a Commando Captain.

World War II brought much misery to many, and to the Wilsons perhaps more than their share. Almost all their paintings of 1938 and 1939, conserved in their Paris studio, were looted or destroyed in the Occupation. In the last days of the war in Europe Paul Bassett-Wilson MC, leading No.3 Troop of the 9th Commando, was killed in Italy.

For a decade and more the grieving Muriel painted not at all. Late in 1946 Bassett accepted an invitation to mount a large retrospective at the Left Bank Galerie du Back, from which the Musée national d'art moderne in Paris bought one of his Chair series "the Chairs" in the Luxembourg Gardens. Again, Wilenski wrote the catalogue introduction, and concluded of Bassett what might with equal reason apply to Muriel "If Bassett's English Muse, afraid of seeming dry and Puritan and stay-at-home, occasionally dons gold and scarlet, emerald and russet skirts, peacock bodices, mantillas and high combs to challenge her adventurous sisters of the Ecole de Paris, we must not reproach her for conduct unbecoming an English lady, but rather applaud her enterprise and courage."

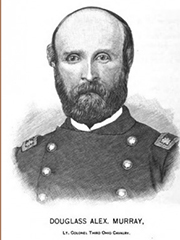

Douglas Alexander Murray 1824-1866

Douglas Alexander was the 11th child of Major-General James Patrick Murray, who had distinguished himself at the battle of Douro in Portugal under Sir Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. The natural course of Douglas’ career would be to follow in the footsteps of his father and his grandfather General James Murray, who led one part of General Wolfe’s army which defeated the French in Quebec in Canada, and subsequently became Canada’s first British Governor. Unfortunately, advancement in the military depended on the system of “purchase” whereby promotion was bought, and therefore required soldiers to have families with sufficient means to support them. Two things were not in favour of Douglas, which eventually led him to give up and chance his luck in America; the first was the premature death of his father, which left his mother and siblings in a precarious state; the second was that he was the 11th child and fifth son, the significant thing being that any young man following such a career would also depend on an influential “sponsor”, which was like a god-parent. By the time it was Douglas’ turn, all those who might have helped had been used up on his elder siblings. Records at the National Archives in Kew show the many impassioned letters Douglas’ mother Elizabeth wrote to various regiments, asking for Douglas to be accepted as a junior officer; but without the money, and despite his very distinguished pedigree, this was to no avail.

The next thing we hear about Douglas is his arrival in the US. It seems that in his efforts to join the Unionist army he slightly re-invented his past, as records state variously that he was born in England and in Scotland – presumably he thought it not advantageous to reveal his birth in Ireland.

Douglas joined the U.S. Army, later, in 1861, joining the 3rd Ohio Cavalry, which he subsequently commanded. He fought in several battles of the Civil War and was severely wounded, losing his left arm. He received the rank of Lieutenant Colonel on October 10, 1861. He resigned June 7th, 1863, but it is not known whether this was on account of his injuries. There are several stories about Murray in the History of the 3rd Ohio Regiment, which show him to be a popular and eccentric character, though not without human weakness.

On his bravery: “The Third Ohio, Lieutenant Colonel D. H. Murray, when the Right broke, also made a handsome dash, and drove the enemy from McCook's ammunition train. Subsequently they charged, saved the train of the Center, drove off the rebels, recaptured a hospital, and captured many prisoners under Colonel Eennett's eye.” “I then proceeded with the cavalry as fast as the roads would permit, and, when getting within about one-fourth of a mile from town, ordered a charge upon the town, which was splendidly executed by Lieutenant-Colonel Murray at the head of his men.”

Of his generosity (which later saved his life!): “Just previous to the battle of Shiloh, the 3rd. Ohio cavalry, commanded at the time by Lt. Col. Murray, took possession of Lawrenceburgh, Tennessee. The people of the place were understood to be all Secessionists, and the Lt. Col. Ordered his men to search all the houses, arrest all the men, and take possession of all guns and other arms…being careful to protect the women and children from all harm and insult. While this was going on, Col. Murray rode down the street, and while in front of the Masonic Hall, noticed that some of his men had been in the Lodge-room and taken possession of some articles belonging to the Lodge. Immediately ordered them to return every article to its place, and then placed a guard at the door to protect the hall from future violation. During the Battle of Shiloh, the Third Ohio Cavalry captured a Confederate Surgeon. The Surgeon asked Lieutenant Colonel Murray if he was not the officer who had saved the Masonic Lodge at Lawrenceburgh, TN from being ransacked and was informed that he was. The doctor then told Lieutenant Colonel Murray that it was that fact alone that had saved him from being ambushed. A Confederate Mason who had witnessed his generous act at Lawrenceburgh had recognized him and ordered his men to lower their guns and let him pass.

On his character: “"On October 22 [1861?] our lieutenant colonel, Douglas A. Murray, joined the regiment, promoted from the Second United States Cavalry. A man of fine appearance, he was to be our authority on cavalry tactics. As his name indicates, he was a Scotchman and had a very peculiar brogue, rolling his r's in a wonderful fashion. He gave his commands in a sharp, crisp way, and while it was difficult to understand his words, the men soon learned to know what he meant, although that singular accent afforded us infinite amusement. He conducted our dress parade at 4 pm, the music being furnished by a drum corps composed of three drummer boys and two Mexican veterans as fifers. Lieutenant Colonel Murray left the regiment in 1863. His farewell address was read at dress parade. Most of the boys were sorry to see him go. The men liked him in spite of his fondness for old Scotch but he would allow it to get the best of him sometimes."

Douglas was survived by his wife and four children, and has descendants in the US to this day.