See also

- Pulteney MURRAY's parents: James Patrick 2 MURRAY (1782-1834) and Elizabeth RUSHWORTH (1783-1865)

- Pulteney MURRAY's siblings: Catherine Anne MURRAY (1804-1895), James Edward Ferguson MURRAY (1806-1834), Harriet Elizabeth MURRAY (1809-1882), Mary Johanna MURRAY (1810-1875), Jane Susan MURRAY (1810-1841), Charles MURRAY (1814-1848), Elizabeth MURRAY (1817-1904), Henry Patrick MURRAY (1819-1855), Cordelia Maria MURRAY (1822-1909), Douglas Alexander MURRAY (1824-1866) and George Don MURRAY (1826-1857)

Pulteney MURRAY (1807-1875)

1. Pulteney MURRAY, son of Major General James Patrick 2 MURRAY (1782-1834) and Elizabeth RUSHWORTH (1783-1865), was born on 9 July 1807 in Galway, Ireland. He was born in 1807 in Perth. He was baptised on 20 December 1809 in Freshwater Church. He was a Major in the Army + Sub Inspector of the Royal Irish Constabulary. He had 1 child. He married Jane MACKENNY on 23 May 1848. He died on 20 September 1875 in Galway. He married Elizabeth UNK.

According to Pulteney's great great niece Pamela Churcher he was known to the family as the man who should have been, but never was, "the third General". This referred to the military success of his father and grandfather, the military traditions of the Murray family, and the disappointment with Pulteney's lack of success in this field. What Pulteney did after he left the army is unknown - it was not thought worth recording by the family, who could only think that he had failed by not remaining a military man.

Pulteney was probably named after Lt. General Sir J. Pulteney, to whom Pulteney's father served when Lt. Gen. Pulteney was Aide de Camp in the 9th Regiment around 1800.

Pulteney Murray was born on 9th July 1807, the third of twelve children of James Patrick Murray and Elizabeth nee Rushworth, the latter from an important and influential Isle of Wight family. The couple had met when James Patrick Murray had been stationed there as a young man. Pulteney was named after Sir James Pulteney (later Sir James Pulteney Murray), whose aid-de-camp James Patrick had been during the British campaign in North Holland a few years earlier, and who had played an important role in the furtherarance of James Patrick’s early career. James Patrick had recently resumed his military career after a short stint (seven weeks, actually) as an MP, a position obtained through his wife’s family connections: James Patrick’s second thoughts about army life were later to be mirrored in Pulteney’s abandonment of his military career shortly before his 29th birthday, a decision that resulted in the disapproval and censure of his family – his descendants learned about him as the Murray who didn’t become a general as had his father and grandfather, and the family records contained almost nothing about him, as if he were better forgotten.

Pulteney’s birth occurred at a time of big political upheavals in Ireland, especially with the Act of Union of 1801, which had brought about the end of Ireland as an independent country, forbidden Catholics (most indigenous Irish) from holding any public office, made the Anglican church the state religion and banned any free trade between Britain and Ireland bringing about a virtually total stranglehold of Ireland by Britain. Also, before the Act of Union, in 1798, there had been a (failed) uprising in support of Catholic Emancipation. Pulteney’s future life was very much shaped by these events, both in his early career in the army, before he went to the West Indies, and later, for the majority of his working life as a middle ranking officer with the newly-formed Royal Irish Constabulary, generally considered to be the world’s first police force, in the modern sense of the word. Pulteney’s work could broadly be said to be part of the vast British machine for subduing the Irish nation. In this context it is interesting to note that Pulteney converted to Catholicism on his death bed; this decision would have been coloured by the whole English/Irish issue, the relations between the two countries, the unequal power struggle between the two, and the matter of where Pulteney saw himself in relation to these political issues - in other words, did Pulteney finally decide that he wanted to be identified as Irish rather than British, did he actually change his religious views, did he make a token change to please his wife, or did he change because he knew that life for his wife and children would be easier in an Irish context if their late father/husband had been a Catholic?

Early Childhood

One of the first mentions of Pulteney is in one of a series of letters written by his father to his mother, when he was about two years old. From the letters comes an overriding sense of homesickness on the part of James Patrick, and a great affection for his children whom he misses. We also learn of the hardships and instability of military life, where soldiers were sent from place to place with almost no notice, and almost anywhere in the world. We also learn of the difficulties that Elizabeth had. She was bringing up three (later twelve) children with an absent husband, living in a place where she had no roots or friends, and also forced to move frequently on account of her husband’s career – Catherine, their first child, was born in Banagher, James, their second, in Tipperary, and Pulteney in Galway. “God Almighty bless, preserve and protect you, my dear Catherine, James and little Pulteney, and kiss them all a thousand thousand times for me and believe me to be ever your most sincerely and truly affectionate husband.” This, and countless other very emotional expressions of affection, testify to his longing for home and real love for his family.

At the age of three, Pulteney experienced the tragedy of his father losing the use of his right arm in the battle of Douro in Portugal, in a campaign run by Arthur Wellesley, future Duke of Wellington. Could the remembrance, at such a young age, of seeing his father return home with a completely shattered arm have influenced his later decision to leave the army? James Patrick, however, continued undaunted with his military life, though not to the same extent as might have been, in charge of the 5th Garrison Battalion (a veteran’s battalion rather than a proper regiment). Yet for his service and undoubted qualities, he was eventually made a major general and created a Companion of the Bath (on the first occasion that that honour was given). So Pulteney, like his numerous siblings, was brought up in a distinctly military ambience, and naturally sought to join the army himself at the earliest age, like the rest of his brothers: of the six of them, three (James, Pulteney and Charles), subsequently had army careers, two (James and George Don) had navy careers, and it is not known want Henry Patrick did. However, the shortness of their lives bears eloquent witness to the hardships of the military life in those days. James died at 28, Charles 34, Henry 36, Douglas 42 and George 31. Pulteney alone, having left the army at the tender age of 29 and joined the Royal Irish Constabulary, in which he served for the rest of his life, lived beyond 50, dying at the (for then) respectable age of 68. In contrast, all but one of his sisters lived to a good old age, with two of them (Catherine and Elizabeth) living until 91 and 87 years respectively! Actually, this was not entirely usual for these times, as often it was the women (as, in all likelihood, Pulteney’s first wife Jane) who died young in childbirth.

Pulteney’s childhood was characterized by the constant growing in size of his family. As the third of twelve children, the last of whom was born when he was nineteen, he cannot have had a great deal of individual attention: maybe he longed for his childhood again, when he was adored as “pretty Pulteney” and when his family had such high hopes for him to follow in the family line.

The Army

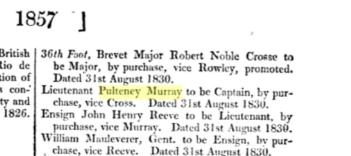

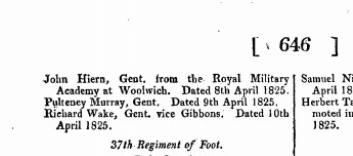

It is not known where Pulteney went to school, but at the age of seventeen he joined the army, becoming an Ensign with the 36th Foot. In 1826 he joined the 36th Foot (with purchase) as a lieutenant, in 1830 became a captain, and, when he sold his commission and left the army in May 1836, was a major. His rise had been steady rather than meteoric, but the ten or so years he had in the army had taken him to most parts of Ireland, Gibraltar, Barbados, Spike Island, St. Kitts, St. Christopher, Antigua and St. Lucia.

A personal connection enabled Pulteney to join the 36th Foot: General George Don was a friend of Pulteney’s father and in fact was responsible for a series of paintings of the latter which still exist in the family, showing James Patrick, with his identifying injured arm, with his regiment. In fact, James Patrick’s 12th child was christened George Don Murray, with General George Don himself acting as sponsor (godfather) and the then 19-year old Pulteney acting as the other sponsor - clearly the family were by that time finding it hard to find sponsors for such a large family. Spike Island, just off the coast at Cork, where Pulteney was stationed with his regiment in 1830, was used as the British Arsenal at the time. During the following decade it became a centre for convicts prior to their departation to Australia and other places. Pulteney also spent time in Fermoy, which was the principal British military base in Co. Cork (In 1806 the first permanent barracks had been built there providing accommodation for 112 officers and 1478 men, as well as 24 cavalry officers, 120 cavalry men and 112 horses). At this time, only 42% of the army in Ireland were Irish, and in fact this reduced in the next thirty years to only 25% - the army was serving British interests. For men (as opposed to officers) in the army, life was very bleak. Marriage was strongly discouraged, and could only take place with the permission of the commanding officer, and in only a few cases would a wife be given permission to be with her husband; in all other cases the army did not even acknowledge the existence of wife or family. Living conditions were sqaulid and cramped, food was bad and insufficient, pay was poor and sanitation almost non-existent (for example, soldiers were expected to wash in their own urine tub). Once a soldier had paid the necessary costs of living and feeding from their pay there was usually little to nothing remaining. It is a little puzzling to wonder why there was a need for the formation of a Royal Commission in 1860 to consider why the army had a recruitment problem!! Life was somewhat better for officers, who were drawn from the upper classes exclusively, through the system of “purchase”. This system ensured the continuation of the “old boy network” but ensured the absolute loyalty of the armed forces, because they were drawn from the ruling classes; the system of purchase of rank did not disappear from the army until the end of the century, and not without a lot of resistance.

Conditions for the Irish civilians were even worse - a visitor to Ireland in the early nineteenth century declared: “now I have seen Ireland, it seems to me that hte poorest among the Letts, Estonians and Finlanders lead a life of comparative luxury”. Even the Duke of Wellington said “There never was a country in which poverty existed to the extent that it exists in Ireland”. The population at this time was growing fast, which was connected to the influence of the Catholic church, and the potato became more and more the staple on which ordinary Irish depended; however, the potato crops were often blighted, leading to hunger and shortages, culminating in the famous and catastrophic famine of 1845. British treatment of the Irish was justified by their view of them as lesser human beings than the Anglo-Saxons. In fact, later in the century, when Darwinian views were hijacked by racial supremacists, pseudo-scientific theories abounded about the Irish being “white negros”, which view reveals the double prejudice against both black and Irish. Pulteney grew up with this background, and would have viewed, along with his British contemporaries, his task as that of controlling the Irish, and would not have encountered views discussing their rights.

From 1832 to about 1836 Pulteney was with his regiment in the West Indies. By this time, it should be noted that Sir George Don had retired from the regiment. One of the places visited by the regiment was Antigua. Here is a description of the Antigua of 1832, the year Pulteney was there: “In 1832, there were exported from the colony equal to 11,010 hogsheads of sugar, 7342 puncheons of molasses, and 1238 puncheons of rum. A considerable quantity of cotton was formerly produced, but its cultivation is now discontinued. Two descriptions of soil are prevalent in the island: one a rich black mould on a substratum of clay, the other a stiff clay on a substratum of marl, which is not so fertile a* the former description of soil. It contains a large proportion of level land, and is not in any part mountainous. The shore is in general rocky, and surrounded by dangerous reefs, which make it difficult to approach, but there are several excellent harbours, in one of which—English Harbour, situated on the south side of the island—is a dock-yard belonging to government, with every convenience for careening and repairing vessels: this harbour is capable of receiving the largest ships in the British navy, and here, during the war, the king's ships on the West India station were usually moored during the hurricane mouths.” What the description does not mention is the matter of slavery, and how the British Army’s role was to protect the huge trade made possible by the free labour provided by the slaves. “In Antigua/Barbuda slavery was abolished in 1834 but it did not “free” the slaves as we understand freedom today, Antiguans continued to be scarred from the colonial experience. Emancipation perpetrated further the hierarchy of colour and race that the British had established at the start of the colonial period. Stringent Acts were passed to ensure that the planters had a constant labour supply”

[http://www.antiguamuseums.org/Historical.htm]. Much of the British Army’s role in the West Indies in the first half of the nineteenth century was to protect the islands and their trade from the French, with whom there were many military and naval encounters. St. Lucia, another place that Pulteney went with his regiment, had been alternately French and British for many years until finally it became permanently British in 1815. In 1836 Pulteney left the army. It is not known whether he came back to Ireland with the regiment first, or whether he stayed in the West Indies until the end of his commission; in any case, it is possibly significant that he left the army just over a year after the tragic and untimely death of his father: perhaps the event made him realize that he was not made for a life in the army; perhaps his father’s death made him wish to return to Ireland and a more settled life; this wish might have been prompted by a wish to be there for his siblings and mother, or simply because he desired it for himself. However, the next chapter of his life, with the newly formed Royal Irish Constabulary, was far from settled, although it did mean that he stayed in Ireland.

Paradoxically, four years after Pulteney left the army, his younger brother (by 17 years) Douglas Alexander Murray was being helped by his by then destitute and desperate mother Elizabeth to join the army. She and Douglas were both writing to everyone she knew in influential circles within the army, using her late husband and late husband’s father’s reputations to beg for a commission for Douglas without purchase (because the family had no money). Finally, in 1841, this was granted, and Douglas started in the .... The letters Elizabeth and Douglas wrote, and their replies, are held in the National Archives in Kew, and provide a poignant reminder of the position of the families of soldiers who have died, and how little help they got from the army. Elizabeth also mentions her oldest son, who had joined the navy, and who had died, and whose wife had also died, leaving their children in her care. “Five years ago he was deprived, by death, of his father who lost his life in consequence of a cold taken in the vain attempt to save the lives of two officers of the Royal Regiment...” One wonders what the effect on his mother was of Pulteney leaving the army, when she had to go to such inordinate lengths of begging to ensure a place in it for her younger son? And one wonders where Pulteney was in all this. It is not entirely clear from the records when Pulteney started with the RIC: his record notes that he was appointed on 11 March 1842 at the age of 30. Actually he would have been 35 at this time. There is further no record of what he did between 1836, when he sold his commission in the army, and 1842: did he undergo training, did he do nothing, or did he do something else; or was the date 1842 incorrect but the age 30 correct, in which case there would have been little or no gap between the two careers.

The Royal Irish Constabulary

A short time after leaving the army Pulteney joined the Royal Irish Constabulary; it seems likely he had a training as a cadet first, and was then posted to the first of six places, Sligo, for a period of just under a year. After this he spent the next six years in Tyrone, then, after a couple of years at Kings, eight and a half years in Westmeath (near to the place where he was brought up), and then finally, after a couple of months at Queens, finished his career in Galway.

Early on in his career with the RIC Pulteney got into a fair amount of trouble. For example, the records show that in 1843 he was “suspended from rank and pay”, though the reason is not given. At this time Pulteney was still a single man. More interestingly, the second half of 1850 was clearly a bad one for Pulteney. In August he was “admonished” (again no reason is stated), in November he is “reported for debt” and again, in the same month, receives an “expression of displeasure for neglecting to patrol at night”. What is most odd is that Pulteney had at this time been married for only two years, to Jane (neé McKenny), about whom nothing is known, and that they had a one-year-old baby, Pulteney Henry. Were the family in genuine hardship, was family life just too much for Pulteney, or did he drink; maybe his wife Jane, who was to die in less than a year, was already ill, and Pulteney could not face it, or did his actions precipitate her ill-health?

After Jane’s death, little Pulteney Henry was sent to live with his Aunt Donny, and it seems likely that Pulteney had no further part in his upbringing. Sadly, he is not even mentioned in his father’s will, made after he had remarried. Pulteney Henry’s descendants, who thorougly documented the family tree and history, pointedly omitted any reference to Pulteney’s second wife, Elizabeth, who was from Tyrone, which is just about all that is known about her. Pulteney and Elizabeth had three children, Georgina Emily, James Alexander and Elizabeth Jane: this is the order in which they are listed in Pulteney’s will, and so is likely to be in chronological order of age.

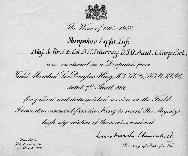

Despite Pulteney’s earlier admonishments from his superiors in the Royal Irish Constabulary, he was, on 15th Jue 1869, granted good service pay; on retirement he was discharged with an annual pension of £180 and a lump sum of £38. He had risen gradually through the ranks of RIC officers, being made a 3rd sub-inspector in March 1842, second sub-inspector in July 1848 and first sub-inspector in April 1858.

Conclusion

It is interesting to note that Elizabeth, at the time of her death in 1898 is stated as being “of Rose Lodge”; yet Pulteney, at his death twenty years earlier is stated as being “of Wood Quay, formerly of Rose Lodge”. This seems to imply that the couple separated, unless Elizabeth moved away from Rose Lodge with Pulteney, but moved back after his death.

Another document exists which is supplemental to Pulteney Murray’s will, and which dates from 1898, just after Elizabeth’s death. This states that the will was not administered, or at least not fully administered, after Pulteney’s death, and provides for the remaining £1350 left by him to be divided between his two daughters “in the United States”. It also gives the names of their respective husbands, Colman Flaridy (who married Georgina), and Michael McCarthy (who married Elizabeth Jane). The questions remain as to why the money was not released earlier, and also what happened to James Alexander Murray, their brother.

36th (Herefordshire) Regt. of Foot

Regimental Notes: Born at Perth on 9 July 1807. 5 April 1825 Ens 36th Ft without purchase. Taken on Depot strength at IOW in Apr 1825, on leave. Shown in May 1825 to Half-Pay List Infantry unattached; however in the 1st Battalion return (Feb 1826) after its return to England he is shown as on leave (private affairs) from 8 April 1825 to 24th May 1826 by permission of C in C so the HP unattached list probably wrong. An entry elsewhere shows him in Gibraltar from 5 June 1825 to 3 May 1826. He joined Bn in May 1826 in England. - 29th August 1826 Lieutenant 36th Ft with purchase. - Moved to Ireland (Mullingar) with Bn in Apr 1827, Dublin (Sep) Philipston (May 1828), Limerick (Oct). Birr (Aug 1829), Banagher (Feb 1830), Birr (Apr), Fermoy (Jun). Stayed with his Coy at Fermoy, as part of Depot, when Bn (6 service Coys) sailed for Barbados in Oct 1830. 31 Aug 1830 Capt. 36th Foot, with purchase. - Still with Depot in Dec. 1830 at Spike Island - Took draft to Bn in Barbados on 29 Dec 1831 arrived Feb 1832, St Kitts (Feb 1833), St Christopher (Mar), Antigua (Jul), St. Lucia (Nov), until he retired on 6 May 1836 by sale of his commission.

He was a Major on retirement.

From: Historical Record of the 36th, or the Herefordshire Regiment of Foot [eyre & Spottiswoode, 1853]

(whilst Pulteney Murray was serving in the regiment)

On the lst of February 1823, the detachment which was stationed at Cerigo arrived at Corfu, and joined the headquarters of the regiment.

In the year 1825, the establishment of the regiment was augmented from eight to ten companies, and formed into six service and four depot companies, consisting of forty-two serjeants, fourteen drummers, and seven hundred and forty rank and file.

The regiment remained in the Ionian Islands until the 2d of December 1825, when it embarked at Santa Maura for England.

On the 18th of February 1826, the regiment disembarked at Chatham; in the spring it proceeded to Colchester, afterwards to Macclesfield, Stockport, Manchester, and Bolton.

During the early part of the year 1827, the regiment remained at Bolton, in Lancashire, and in April it proceeded to Liverpool, from which place it embarked for Ireland on the 14th of that month. The regiment arrived at Dublin on the following day, proceeded from thence to Mullingar, and returned to Dublin in August following, where it was stationed during the remainder of the year.

In May 1828, the regiment proceeded from Dublin to Naas, and in October it was removed to Limerick.

The regiment remained at Limerick until August 1829, when it proceeded to Birr, and continued during the rest of the year at that station. Lieut.-General Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe, Bart, was appointed Colonel of the THIRTY-SIXTH regiment on the 21st of December 1829, in succession to General Sir George Don, G.C.B. and G.C.H., removed to the Third foot, or the Buffs.

In June 1830, the THIRTY-SIXTH regiment proceeded from Birr to Fermoy, and was formed into six service and four depot companies. The service companies embarked at Cork on the 11th, 13th, and 14th of October for the West Indies. The depot companies remained at Fermoy for a short time, and were afterwards stationed at Spike Island. The service companies disembarked at Barbadoes on the 20th, 21st, and 28th of November.

The service companies suffered severely during the great hurricane in Barbadoes in 1831, having eleven men killed, and several severely injured.

The depot companies were removed from Spike Island to Charles Fort, Kinsale, in October 1831, and continued there during 1832.

The service companies which had, since their arrival in the West Indies, remained at Barbadoes, were removed to Antigua in February 1833. The depot companies proceeded from Charles Fort to Ballincollig in January 1833; to Cork in February; to Templemore in August, and to Nenagh in October following.

During the year 1834, the service companies remained at Antigua. The depot companies were removed in October from Nenagh to Limerick.

In November 1835 the service companies proceeded from Antigua to St. Lucia. The depot companies quitted Limerick for Galway in May 1835, and marched for Cork in June following, where they embarked for Plymouth on the '14th of September; during the remainder of the year they were stationed at Devonport.

During the year 1836, the service companies remained at St. Lucia, and the depot at Devonport.

In February 1837 the service companies proceeded from St. Lucia to Barbadoes. The depot companies were removed from Devonport to Kinsale in June 1838. On the 10th of November 1838, the service companies embarked at Barbadoes for Nova Scotia, and arrived at Halifax on the 8th of December.

From Pulteney's will it is now known that he lived first at Rose Lodge, Spiddal/Spiddle and subsequently moved to Wood Quay, Galway, and that he worked as a sub inspector in the Royal Irish Constabulary. It is also now known that he remarried and had two daughters and one son; both duaghters subsequently moved to the United States. It is interesting to note that the family of his first wife made no record of Pulteney's remarriage and the children therefrom, despite thorough records otherwise being kept.

Furthermore, although no record has yet been found of the birth dates of the three children, the order given here is the order given in Pulteney's will. Given that the son is listed in the middle, it is more than possible that the order is that of age. In addition, when the will was properly administered in August 1898 (obviously some unfinished business in 1875), on the occasion of the death of Pulteney's wife Elizabeth, James Alexander Murray (Pulteney's son) was not mentioned, perhaps impyling that he had died. It is also worth noting that Pulteney's will makes no provision whatsoever for his son by his first marriage, Pulteney Henry Murray.

Lastly, in 1895, at her death, Elizabeth Murray is stated as being "of Rose Lodge", and yet her late husband Pulteney, at his death in 1875, was said to be "of Wood Quay, formerly of Rose Lodge", seeming to imply that the couple had separated before his death.

The question remains why the will was not administered in 1875, but had to wait a full twenty years, when the two daughters in America laid claim to the relatively small sum of £1350 left by Pulteney (that part of the will which was left unadminstered until 1898).

Notes on the Royal Irish Constabulary, in which Pulteney Murray pursued a career after leaving the army.

The first organised police force in Ireland came about through the Peace Preservation Act of 1814 but the Irish Constabulary Act of 1822 marked the true beginning of the Irish Constabulary. Among its first duties was the forcible seizure of tithes during the "Tithe War" on behalf of the Anglican clergy from the mainly Catholic population as well as the Presbyterian minority. The act established a force in each barony with chief constables and inspectors general under the control of the civil administration at Dublin Castle. By 1841 this force numbered over 8,600 men. The force had been rationalised and reorganised in an 1836 act and the first constabulary code of regulations was published in 1837. The discipline was tough and the pay poor. The police also faced unrest among the Irish rural poor, manifested in organisations like the Ribbonmen, which attacked landlords and their property.

The new constabulary demonstrated their efficiency against Irish separatism with the putting down of the Young Ireland uprising led by William Smith O'Brien in 1848. There then followed a spell of relative calm. However, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, founded in 1858, planned an armed uprising against British rule. This rose into direct action in with the Fenian Rising of 1867, marked by attacks on the more isolated police stations. This rebellion was also put down fairly easily, as the police had infiltrated the Fenians with spies and informers. The loyalty of the constabulary during the rising was rewarded by Queen Victoria granting the force the prefix 'royal' and the right to use the insignia of the Most Illustrious Order of St Patrick. The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) presided over a marked decline in crime in the country with the rural unrest of the early nineteenth century (characterised by secret organizations and crimes such as unlawful armed assembly) being replaced by relative misdemeanors such as public drunkenness and minor property crimes.

By 1836 this force had grown to around 5,000 men and by 1841 this had risen to a total of over 8,600. and from its inception the Irish constabulary was a barracked force. It was spread thinly throughout the country, with four or five policemen living in each barrack the norm.

Ireland in the first half of the nineteenth century was the pioneer for policing, acting almost as a laboratory for its development. With Irish society volatile, disordered and disorderly, the establishment of a uniformed, professional police force for the maintenance of law and order was an absolute necessity. It was the nature of collective violence and the weakness of previously existing forces for social control that led successive governments, from the early 1800's on, to press ahead with the establishment of a centrally controlled armed constabulary. The constabulary in Ireland served as a model for the establishment of a policing system in the rest of the British Isles, and ultimately even further afield in the developing colonies of the Empire. Throughout the 19th century the constabulary continued to develop as a police force. The evolution of the force was characterised by improvements in rank structure, training, and the rules and regulations governing the duties, conduct and discipline expected of the men. One of the most significant developments in the history of the constabulary during the 19th century was its redesignation as the Royal Irish Constabulary, making it the first 'Royal' police force in the British Empire.

Life in the constabulary during the 19th century could certainly, on occasions, be difficult. There was periodic agrarian unrest and constant simmering discontent in relation to the land question, particularly in the south and west. Indeed the dominant image of the R.I.C. for many people often stems from its responsibility to give protection to bailiffs executing distress warrants and evicting tenants, an unpleasant duty that was greatly disliked by members of the force (most of whom were themselves from a rural background). Nevertheless, the duties of the averagepoliceman were otherwise usually varied and uncontroversial.

These extensive civil and local government duties as well as routine patrolling in their districts ensured that the police constable was a very familiar part of daily life, someone with whom people would expect to have regular contact. It was the constable's job to acquire a thorough knowledge of his district and good relations with the local community made this easier. Indeed, good community relations, then as now, were essential for effective policing.

By the end of the 19th century there was a total of around 1,600 barracks dotted around the Irish countryside and some 11,000 constables. The territorial division of county and district on which the command structure had been based since the 1836 reorganization continued throughout the life of the R.I.C. Each county was supervised by a county inspector, with the counties sub-divided into a number of districts, each headed by a district inspector. They in turn were assisted by a head constable based at the district headquarters, on whom rested the main responsibility for operational policing and the conduct of the men in the barracks. There were a number of barracks in each district, usually with a sergeant and four constables.

The R.I.C. was characterised by a strict code of discipline. There was no official system of duty, rest days or annual leave, and in the interests of political impartiality members were even banned from voting at parliamentary elections. There were strict instructions laid down in police regulations concerning standards of conduct and appearance (for example, at one time police were absolutely prohibited from entering a public house socially). Other regulations were principally designed to maintain the standing of the police within the community. Members were forbidden to marry until they had at least seven years service and any potential bride had to be vetted by the constabulary authorities to ensure her social suitability. It was forbidden for policemen and their wives to sell produce, take lodgers or engage in certain forms of trade (for example, wives could be dressmakers but could not employ apprentices).

Jane MACKENNY, daughter of J MACKENNY ( - ), died on 19 October 1851. She and Pulteney MURRAY had the following children:

| +2 |

Elizabeth UNK died on 4 January 1898. She and Pulteney MURRAY had the following children:

| +3 | |

| +4 | |

| +5 |

Second Generation

2. Colonel Pulteney Henry MURRAY, son of Pulteney MURRAY and Jane MACKENNY, was born on 17 November 1849 in Edenderry, Queens County, Ireland. He was a Colonel in the Army. He married Mary Leaycraft INGHAM on 20 January 1876 in Hammersmith Ch., London, England. He died on 15 September 1912 in "Mangroville", Paget, Bermuda. He died in November 1912.

1849-1912. Only child of Pulteney Murray and Jane MacKenny, who died when he way about two. He was brought up by his aunt Catherine Anne - "Aunt Donny", whilst his father remarried and had three children. Before any of these children appeared his father had joined the Royal Irish Constabulary - on the official documents for the RIC he left the space for information about any children blank. It paints a rather bleak picture of his childhood that his mother had died and his father wanted nothing to do with him. (17/11/1849 Edenderry, Queens County - 1912) (1877 lived in Parsonstown. in 1901 lived at The Grove, Lancaster. Married Mary Leaycroft Ingham 20/1/1876, St. Paul's Hammersmith; lived at 2 Adelaide Road, Hammersmith at time of marriage). Military career with 1st Shropshire Light Infantry. Its Commanding Officer 1894. Ensign 53rd, February. 1869. Musketry-Instructor,1877 to 1880. Adjutant. 1881 to 1883, including the Egyptian War. Commanded 2nd Battalion, February, 1894, to 1898. Worked in Canada, West Indies, Bermuda, Egypt and Malta. 5' 8 ?"! (85th Regiment (2nd KSLI)).

The Obituary of Pulteney Henry Murray:

"The death took place on Sunday at Southsea of Colonel Henry Murray. Colonel Murray served through the Egyptian War of 1882 as captain and adjutant in the King's Own Shropshire Light Infantry, and was awarded the medal and Khedive's Bronze Star. In 1900 he was appointed to the command of the 4th Regimental District, and afterwards he held the command of the North-Western District at Chester."

Despite this obit. Murray actually died in Bermuda, at his wife's family home, according to various other sources.

In Bermuda - 1870 to 1875. 53rd (Shropshire) Regiment. (later, King's Shropshire Light Infantry).

A note on Khedive's Bronze Star, which was awarded to PHM

The Khedive of Egypt presented a bronze star to all Officers and men of the Navy and Army who were engaged in the suppression of the rebellion of Egypt in 1882. The Star was re-issued for 1884, 1885-6, 1886-9 and 1890. One clasp was issued with an Arabic inscription to those who fought at Tokar on Feb 19th 1901.

Most of the battles in the final years of British influence in Egypt were rewarded with issues of the Egyptian Medal, but the Egyptian Khedive Tewfik Pasha showed his gratitude for British help with issues of his own bronze star for the campaigns in his kingdom.

One of these, the siege and capture of the Mahdist stronghold of Tokar in the Sudan, was unusual in that no British award was made for it, although the Khedive's Star could be worn in uniform. Tokar had since 1883 been the seat of the Beja leader Usman Dinga, and the 1891 campaign resulted in his briefly being captured.

Those who had already been awarded a Khedive's Star for earlier Egyptian campaigns were awarded only the bar for the Tokar campaign; issues of new undated stars with this bar are comparatively rare, therefore, as they went only to the newest soldiers in the forces involved. One such must have received this medal, but as it is unnamed, we do not know who he was. Lester Watson acquired the medal at some point before 1928. (see illustration).

Mary Leaycraft INGHAM, daughter of Hon. Samuel Saltus INGHAM (1816-1900) and Margaret Richardson LEAYCRAFT (1821-1880), was born on 22 June 1848 in Paget, Bermuda. She was born on 22 June 1848 in Paget, Bermuda. She was baptised on 1 October 1848 in Paget Bermuda. She was christened on 1 October 1848 in Paget. She died on 30 April 1890 in "Mangroville". She and Pulteney Henry MURRAY had the following children:

| +6 | |

| +7 | |

| +8 | |

| +9 | |

| +10 |

3. Georgina Emily MURRAY, daughter of Pulteney MURRAY and Elizabeth UNK, died in USA. She married Colman FLARIDY.

Colman FLARIDY died in USA.

4. James Alexander MURRAY was the son of Pulteney MURRAY and Elizabeth UNK.

5. Elizabeth Jane MURRAY, daughter of Pulteney MURRAY and Elizabeth UNK, died in USA. She married Michael MCCARTHY.

Third Generation

6. Pulteney Charles Rushworth MURRAY, son of Colonel Pulteney Henry MURRAY and Mary Leaycraft INGHAM, was born on 1 April 1877. He died on 3 May 1882.

7. Colonel Bertie Elibank MURRAY DSO, son of Colonel Pulteney Henry MURRAY and Mary Leaycraft INGHAM, was born on 10 May 1881 in Chatham. He was a Soldier. He married Agnes Letitia BARRINGTON on 30 June 1927. He died on 14 September 1960.

First Batallion Kings Shropshire Light Infantry.Commanded 158th Royal Welsh Infantry Brigade (TA). Served in Somaliland 1908-1910, First World War( Mentioned in Dispatches five times, and received a DSO) and in World War II commanded 38th Divisional School.

Letter written 14/5/1960 to "Crumbs" (who?), just a few months before his death:

Dear Crumbs,

.......... Hope you have more or less settled in, Maria well, but she does far too much, but who could keep her quiet!?

We go Portcawl on 25th for 15 days. The doctors have not defeated my ailments, and am getting a bit fed up with them, as don't think they take much interest in panel patients, but pills at 3/9 each, 3 times daily, a ???? at 3 guinees a time are a bit too steep for me.

I went to Slim Bridge (Wild Fowl Trust) on Wedensday, most interesting although geese had gone North. Also went Shrewsbury today week back for a Regimental Reunion. Nothing happening here.

Yours,

Bertie.

Agnes Letitia BARRINGTON nee Evans was born on 28 July 1883. She died on 22 November 1964.

8. Lieutenant Percy James Alexander MURRAY, son of Colonel Pulteney Henry MURRAY and Mary Leaycraft INGHAM, was born on 30 May 1884. He was a Soldier. He died in 1920 in Australia.

Was a Lieutenant in the Dorset Regiment and Australian Imperial Force. He died in Australia.

9. Catherine Gladys MURRAY (known as 'Gladys'), daughter of Colonel Pulteney Henry MURRAY and Mary Leaycraft INGHAM, was born on 18 January 1886 in Oswestry (registered). She was born on 18 January 1886 in Oswestry. She married Maurice Fiennes Fitzgerald WILSON on 4 August 1914 in St Judes, Portsea, Portsmouth, England. She died on 12 April 1958.

Gladys was born into a family with a long and distinguished history on her father's side, and into a powerful Bermudan shipping family on her mother's side. Her mother's father had risen to the position of Speaker of the House of Assembly in Bermuda. Gladys herself married a naval officer.

Captain Maurice Fiennes Fitzgerald WILSON DSO, RN (known as 'Fiennes', and also as [unnamed person]), son of Maurice Fitzgerald WILSON (1858-1945) and Florence May BADNALL (1858-1941), was born on 22 June 1886 in 2 Talbot Villas, Old Dover Road, Gravesend, Kent. He was a Naval Officer. He died on 16 February 1975 in Watlington, Oxon. He was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery. He and Catherine Gladys MURRAY had the following children:

| 11 | Pamela Fiennes WILSON (1918-2018). Pamela was born on 17 March 1918. She died on 24 April 2018. She was buried on 8 May 2018 in St. Peter's, Hinckley. |

| 12 | Peter Fiennes WILSON (1920-1995). Peter was born on 21 December 1920 in 2 Dartmouth Place, Blackheath. He was born on 21 December 1920 in 2 Dartmouth Pl., Blackheath. He was a Consultant Civil Engineer. He married Iris Margaret MARTIN on 21 May 1949 in Ilminster Church. He died on 31 July 1995 in Warwick Park, Tunbridge Wells. He died in 1996 in Warwick Park, Tunbridge Wells. |

10. Captain Gerald Graham MURRAY-MOORE, son of Colonel Pulteney Henry MURRAY and Mary Leaycraft INGHAM, was born on 17 September 1888. He was a Soldier. He married Lilian Julietta MOORE on 13 March 1922. He died on 8 July 1949.

Was a Captain in the York & Lancaster Regiement. Assumed by Royal License the additional name of Moore in 1931.

Lilian Julietta MOORE was born circa 1870. She and unk MABSON were divorced circa 1904. She died on 7 November 1953.